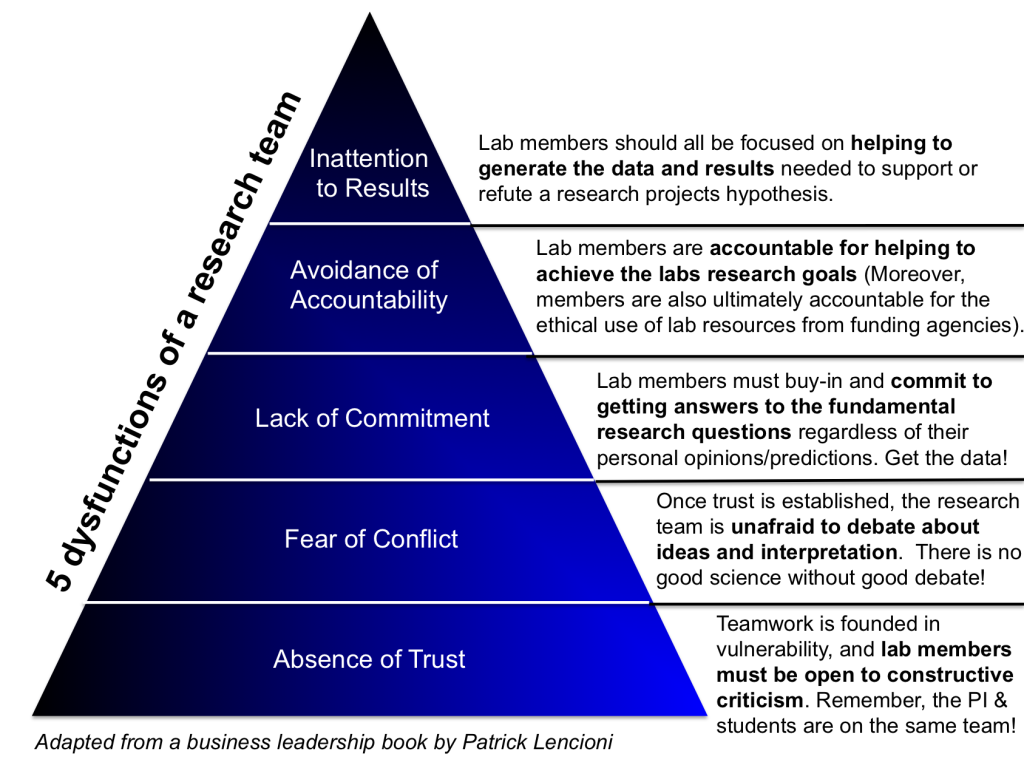

Avoiding the 5 dysfunctions of a team in a biomedical research lab

One of the biggest problems with becoming a lab principal investigator (PI) is that we don’t get any of the training that business leaders get about managing the people and resources of our new labs. I am always going on and on about how academic PI’s really need to get an MBA as a part of their career development. In fact, my post-doctoral advisor did just that and earned his MBA while I was a part of his lab team. Not having an MBA myself, I am always alert to useful nuggets from the business world that can help me as I learn to grow and manage my own lab. Patrick Lencioni published a book describing the 5 dysfunctions of a team (http://www.tablegroup.com/books/dysfunctions) that I find extremely useful for helping my research lab achieve success.

Here is my adaptation of Pat’s model for application to managing my own biomedical research lab team:

3 ways to overcome “Inattention to Results”:

- Publication of results. The scientist’s version of “Your name up in lights!”. Each lab members work can be constantly re-focused around the publication or manuscript it will be a part of. This can be done pretty early on in the project as a way to guide and direct the experiments to be done.

- Results based rewards. If having your name on a publication isn’t reward enough then getting the degree should be. This reward based on results is already built-in if your graduate program has a “No graduation without publication” policy like most.

- Set the tone with a focus on results. Always be on the look out for results. Some students get frustrated when experiments don’t work and will switch to trying this new and fabulous thing they read about to avoid the failure of not being able to get THE needed experimental result completed. For students who get sidetracked or distracted easily, you can refuse to buy reagents for other experiments until the results for one set of experiments are completed appropriately.

3 ways to overcome “Avoidance of Accountability”:

- Write down the expectation of goals and standards for each lab member. This will be different for a PhD student, versus a post-doc, versus a lab technician. It’s important that each member have a road map of what is expected of them. Most PhD programs have this built in to the program with the minimum requirements to degree. I also have a “PhD skills” rubric that I go over ever couple of years with my PhD students so they will know how they are progressing on the development of the necessary skills (see http://cloudworks.ac.uk/cloudscape/view/2014 for useful rubric items). When you hire a lab technician, an explanation of job expectations is usually required upon hiring, so be sure to keep them handy and discuss them with your technician as needed.

- Have weekly progress meetings. Most students need this in order to be accountable for their time. Without it they can will the days away. As much as I like to give everyone the freedom to work independently I have come to accept that a standing weekly update is a powerful motivator of accountability for most. Otherwise I get nothing except a “Hi!” in the hallway. Our research funding agencies don’t accept “Hello” as sufficient for the required progress reports!!

- Monthly ‘research in progress’ meetings with the whole group can help the team serve as the first accountability mechanism. No one wants to present in front of the group with the same exact data they had last month. A whole month has gone by! Most students also work to make the data a little prettier in its presentation on the screen than they would if it’s just a piece of data on paper in my office.

3 ways to overcome “Lack of Commitment”:

- Create deadlines for completion of experiments, writings, conference poster drafts, presentation drafts, dissertation drafts. Everything. You actually have to state when you expect to see the item. In writing via e-mail usually works best. Then it is up to the team member to let you know if they will be unable to make the deadline.

- Discuss worse-case scenarios. I can see some students fear to perform an experiment because they are worried what will happen if it doesn’t work out the way we predict. This is science. So in most cases that is perfectly ok (and likely to happen) and may lead to a new idea about how something is working. Reassure them that a “non support of hypothesis” doesn’t mean it is not a worthy result. If the controls are all there, and working, then you should have an answer that you can share. Even if it’s not what we originally thought. Its ok. We were wrong! We won’t get sued for being wrong in our initial hypothesis, I promise.

- Certainty is needed. A decision needs to be made about the data and research results. I am constantly having to remind my students to put a conclusion about the data on the actual slide or piece of data. Don’t just show data without your conclusion about it. The group can modify and edit it as needed but we need to draw a conclusion about what the data is telling us with certainty.

3 ways to overcome “Fear of Conflict”:

- First, as PI you need to exercise some restraint when mediating conflict. Though you may be thoroughly enjoying the debate make sure that no members feel personally attacked. The easiest way to do this is to make it feel more like a philosophical or educational debate. Or remind everyone that an outside reviewer may ask the same types of questions and that WE as a TEAM need to take this opportunity to think of answers for them.

- Mine for conflict. If no one on a team is bringing up points of conflict a nudge from you might help (i.e., Kris, what do you think of that result? Can you think of anything that could make it stronger?). There is no good science without good debate and conflict! Artificial harmony doesn’t help the groups’ science get better. Productive debate is great for science. This should NOT be an attack on a person. Remind the group of this fact, and encourage the debate towards a productive end (I think “real-time permission” is the fancy term for this).

- Know your people enough to know how they will respond to conflict so that you can keep the debate focused on the goal. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) defines five different modes for responding to conflict situations based on the two basic behavior dimensions of cooperativeness and assertiveness: http://www.kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki

2 ways to overcome “Absence of Trust”:

- Demonstrate vulnerability as a leader. Be humble and be the first to admit when you make a mistake. I am always asking my team for help and have admitted more times than I’d like to admit when I make mistakes. I’m wrong sometimes! So sue me.

- Personal history exercise. The reality is that I can’t do all the great science I want to do alone. I have to have help from others and I need to trust that they want the same things for our lab that I do. The more you understand about people the less likely you are to judge them and to lose trust in them. The personal history exercise seems like a simple way to begin or reinforce the foundation for trust. http://www.tablegroup.com/imo/media/doc/Personal_Histories_Exercise.pdf

I have to admit. I haven’t done this one with my group yet. Hey guys, guess what we are doing in lab meeting next week :-)!!

Based on book and teachings by Patrick Lencioni.

This slideshare does a good job at breaking down ways to manage each dysfunction (intended for a business audience). http://www.slideshare.net/daniellemacinnis/teaming-workshops

Leave a Reply